Thomas Staniforth & Co. Sickle works at Hackenthorpe.

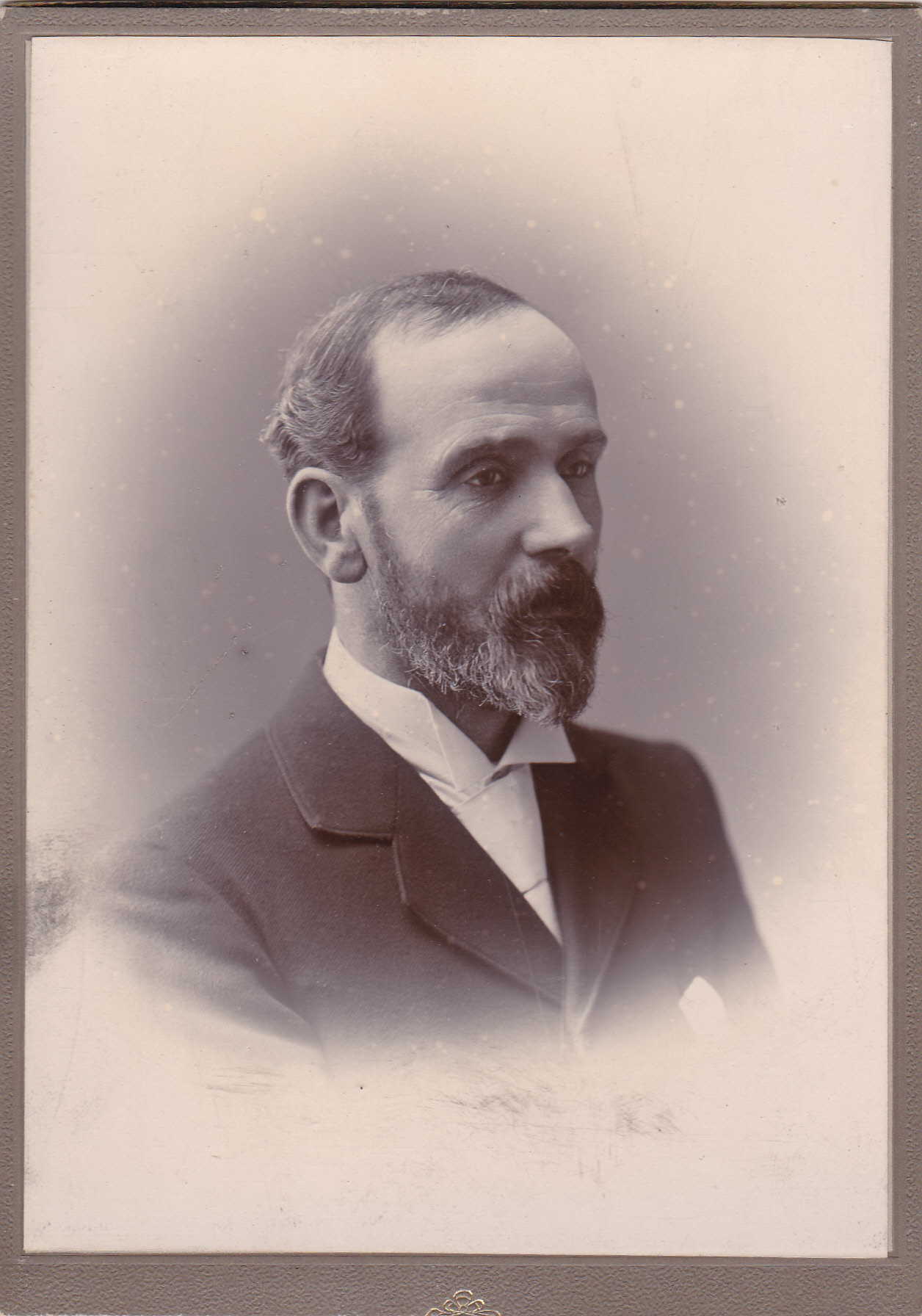

William Staniforth

William Staniforth

William Staniforth, the son of John Staniforth and Mary Carnall was born in 1840. His father apprenticed him when he was 14 years old to two die-sinkers from Sheffield. Robert Braisford Townend, a man that lived in St. Philips’ Road in Portmahon, which today is the Netherthorpe area of the city, and Edwin Arthur Schofield. He was apprenticed here for six years and five months, and after the first year he earned the sum of eight shillings per week. Such weekly payments to be made on the Saturday of Every week so long as the said apprentice shall be at his said Masters’ command and that for Ten hours per day (Sundays Excepted) in Health and in Sickness (sickness by God’s will and Not by Improper Habits) and to be in Lieu of Finding and providing the said Apprentice Meat, drink, washing, lodgings, Clothes and all other Necessaries whatsoever, including Medicine, Medical and Surgical aid and attendance Fitting and Meet for such an Apprentice – and that the Said Masters Shall and will pay and allow the Said Apprentice the Sum of One Shilling per year for Wages during the said Term and that the said Apprentice shall only be required to work Nine hours per Day for the First Seventy Four weeks of his term of Apprenticeship also that the said Masters shall not Require the said Apprentice to work the Turning Wheel Nor go Errands with the Wheelbarrow.

This document is then endorsed when the apprenticeship was completed, on William’s twenty first birthday, on December 5th. 1861. Following this William was self-employed for a period, basing himself at the top of High Street, Sheffield, in 1870 he took up a position as die-sinker, modeler and designed for the silversmiths Fenton Brothers at their South Moor Works on Earl Street, this is where he remained until his death.

William’s elder brother John Staniforth married Frances Sarah Hawke, the daughter of silversmith Thomas Hawke, and it is interesting to note that their two eldest sons, John Edwin Staniforth and Thomas Hawke Staniforth are described as ‘Silver-smith’ and ‘die-sinker’ respectively.

As mentioned in our article on William’s parents, his father moved from Woodhouse when they bought the Wellington Inn, this would have been shortly after William finished his apprenticeship. Thomas Hawke was at onetime victualler of the nearby Duke of York and the former owner of The Wellington Inn was his brother-in-law William Hardcastle.

William Staniforth married twice, his first wife was Sarah Parkin, the daughter of William Parkin, a pen-blade grinder. Sarah was adopted by her aunt Mrs. Swan, whose husband was a Grocer on Broad Lane, Sheffield. Mrs. Swan would outlive her husband before going onto marry twice more, first to Mr. Jackson and then when he passed, she married Mr. Siddall, he also passed away before her.

Through the writings of Mrs. Rosamund Du Cane, William’s Great-Granddaughter, we are able to provide details from the diary of his son John William Staniforth, better known as Jack.

‘one of the best, if not the best die-sinker that Sheffield ever produced’ he writes, a well respectable and respected man, an ardent Liberal, a staunch Nonconformist, deacon of the ‘Tabernacle’ and at one time ‘Quite the most prominent and most popular figure in the congregation’ a proud man and a loving father. Rosamund also notes that he writes lovingly about both of his parents, mentioned how his mother taught him to read and write and how his father helped him with his homework, studying his school books after he had gone to bed, making sure to keep a page or two ahead of his son, she also points out that his education at Woodhouse had not lasted long, as he was apprenticed by age fourteen.

In 1870, Jack writes about his parents again ‘They were a home-loving couple and did not often leave their own fireside. Mother sitting by the wire, sewing, knitting or darning: father sitting at the table, making penciled designs of tea-pots, cruets, patent pocket knives etc. this is the mental picture I have of evening home life in 1877’

William Staniforth in younger years

William Staniforth in younger years

William Staniforth and Sarah Parkin had the following children:

Mary Staniforth was known as ‘Eppy’ during childhood, ‘Pollie’ during teenage years and as an adult was referred to as ‘Myah’.

When William married Sarah he was twenty three years of age and she was twenty two, in the photo we have of him we see a man with dark wavy hair, parted in the centre with a beard. Mary Staniforth, their daughter noted how Sarah adored him, and pandered to his every need, at the time of their marriage she was already pregnant with their son. The pair also had children that passed as infants, from Smallpox, and Jack himself was once confined to the room where his infant siblings and his own mother were dying.

At this time William was on his way to becoming Managing Director at Fentons and the married couple were both pillars of the local chapel. The Maxfield family was another family that attended the chapel, and the head of this family would go onto purchase the Fentons firm. Mary Staniforth refers to the Maxfields as ‘Oatmeal coloured’ giving the impression she thought they were rather dull. William however appeared to think otherwise as Alice Maxfield caught his eye. In Mary’s words, relayed by Rosamund Du Cane, Alice apparently told William that she ‘understood’ him and that his wife did not. Sarah by this time was a middle aged, ailing woman, and was no competition for Ms. Maxfield. Sarah became jealous of the new woman, and she turned to alcohol. It is said that this drove her out of her mind, and began shrieking around the house, shook dusty mats over the clean floor and it was said she used foul language. Servants refused to stay in the same house as her and young Mary Staniforth was taken out of school to run the house, Jack states ‘our sister-mother. Not for her music and singing and painting. She was taken away from school when little more than a child herself to become the mother of the family… and right loyalty and nobly did she fill the place’.

One morning, when the house was empty save for Sarah, Mary and her sister Edith, Sarah began to hemorrhage. Edith left to fetch the doctor. Mary stayed and tried to save her mother, but before the doctor arrived at the home, Sarah died in her arms. Word was sent to Jack, who was in London at the time attending St. Thomas’s Hospital as a Medical Student ‘Mother very ill. Come home at once’. He arrived home about four o’clock in the afternoon, but his mother had already passed.

Since the death was so sudden, there was a Coroner’s inquest. Mary was called as a witness and she was asked ‘Do you consider your father’s association with Miss Maxfield had anything to do with your mother’s death?’ The family doctor came to her aide, proclaiming ‘Miss Staniforth is my patient and I consider her too young to answer such a question’.

Jack told Alice Maxfield, who was only a year older than himself, to leave them in peace. She listened but within days she returned. It was said that the local neighbours hissed and spat at William as he climbed into the carriage to attend Sarah’s funeral, knowing full well of the scandal.

Sarah Staniforth (nee Parkin)

Sarah Staniforth (nee Parkin)

It is interesting to note that Jack himself did not write about this time period at all, however he remained close to his father, writing that when he was close to death he told him ‘Ah, my lad! You were all the world to me once. We’ve been more like brothers than father and son haven’t we?’

Mary Staniforth would go onto encounter another tragedy in her life in September 1893. She and a friend went to a local fair in Sheffield, there they found a fortune tellers tent. Her friend entered first, she emerged with a content look on her face and Mary decided to enter herself. The fortune teller looked at her hand but was reluctant to say a word. Mary pushed her to explain herself, she said ‘Someone you love dearly is going to die, very soon, away from home’ Mary began to think of her sister Kate, a girl who would have been nineteen at the time, she mentions she had red-gold hair that ‘shone like burnished gold’. Kate was staying with her grandmother at the Wellington Inn at this time. Mary returned home, and she was told to go to Darnall as Kate had taken ill. She raced to the Wellington Inn, however it was too late, Kate had passed away. It is said that on her deathbed Kate sat up in bed and proclaimed ‘Mother, I am coming’. Jack noted that the official cause of death was pneumonia, but he was dissatisfied with this. Kate, just like her mother and sister Alice suffered from a weak heart and the viral pneumonia would have proven fatal.

Three months later William married Alice Maxfield.

The surviving sisters knew that the only way they would escape the household now would be through marriage. Edith and Mary’s sister Alice Staniforth married first. She married nine months after Kate’s death to Arthur Joseph Cooke, a bank clerk. Mary married Frank Thornton Addyman, President of the Harris Institute in Preston at the time. He was said to have a brilliant brain but a weak character, he had been in love with Mary for years. However she soon found herself having to dig him out of multiple financial messes and by the time their only daughter was in her teens, Frank was drinking heavily.

Edith did not marry until 1902, she married Frank Newell. This marriage was far more positive and Franks work saw him making regular trips to Spain. Edith and her husband setup their home in North Yorkshire, across the road from their brother Jack in the North Yorkshire village of Hinderwell, just outside of Whitby, and their kids grew up together.

When Arthur Cooke was let go by his employers in 1906 for outrageous behavior, Jack felt the need to stay silent in his journal. Jack actually paid off Arthur’s debts in return for his signing a deed of voluntary separation from Mary. Frank Newell joined him and paid for the upkeep of the three small children, Kathy and twins Clifford and Margaret, whom Alice now had to bring up on her own. She did this by teaching and working as a dressmaker. Alice died at the age of forty one, and Mary took in Margaret and Clifford and Kathy went to live with the Maxfield sisters.

At this time, William had died, only nine years after marrying Alice Maxfield. A respiratory problem had weakened him, and heart disease once again played its part. He was also grief stricken at the death of his second son Harry in August 1901 and was beginning to worry about money. Now the man that was always noted for being so precise and full of pride was leaving bills unpaid and letters unanswered. Jack noted that he ‘drifted down the weary days with a complete lack of interest or aim’. He passed away after several months of illness on May 7th 1902. Alice Maxfield was also ill at this time and it seems likely William was also suffering from anxiety due to her health. They were staying at a home that belonged to the Maxfield sisters at Matlock Bank, they moved here in the hopes that William would regain his strength after an attack of bronchitis.

By this time Jack’s own son was due to leave for school in Windermere, however he knew that his father was gravely ill, and if he did not take Max to see his grandfather now, he would likely never see him again. Jack arranged for his son to be taken to Matlock, dressed in his new suit. Family tradition states that when he arrived, William placed a half a crown in his grandsons pocket, Max bought a conjuring set with this money and would perform tricks for his grandfather, who would sit in a chair with a blanket over him.

Kate Staniforth

Kate Staniforth

Following William’s death, his wife went to live with her sisters, all still unmarried and when she died eighteen years later, she left everything to them, nothing to the family of her husband.

Rosamund Du Cane makes an interesting observation in her writings, Jack never makes reference to his cousins, the children of John Staniforth and his wife Frances Sarah Hawke, which is interesting as they too lived in Darnall and were in the same line of business, the only mention of John is a few months after his mother passes away, he states ‘…bitten with an antiquarian and genealogical craze I bombarded father, grannie & Uncle John with questions’ there is no other mention following this.