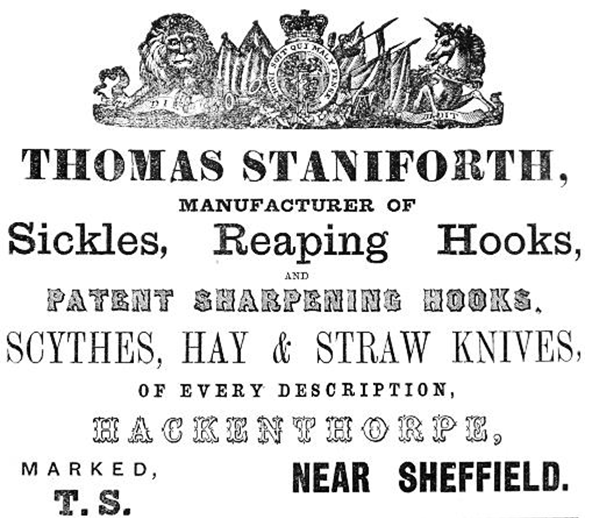

Thomas Staniforth & Co. Sickle works at Hackenthorpe.

Samuel Staniforth's mark on his own will dated 1756.

Samuel Staniforth's mark on his own will dated 1756.

On the 1st of May 1704, Samuel married Mary Tompson at the Sheffield Parish Church, today known as the Sheffield Cathedral. Throughout their married life, the couple have a total of five sons and four daughters, with only one of the sons passing in infancy.

When we look at Samuel’s life in the village of Hackenthorpe, in Beighton parish, he would appear to have lived a typical Sickle smith’s life. He spent his day in his smithy, while also running his farm in the off months.

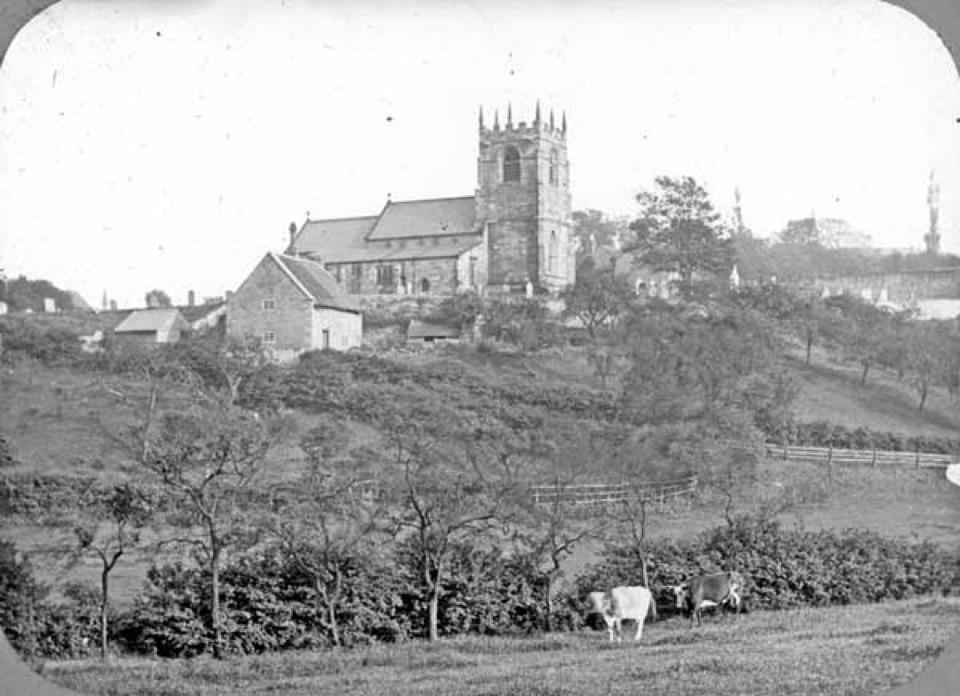

St. Mary's Beighton as it appeared in the early 20th Century.

St. Mary's Beighton as it appeared in the early 20th Century.

A Manor court roll dated September 1708 shows Samuel being threatened with a fine of 3s and 4d if he didn’t ‘Scower his ditch by Robinson Close side well and sufficiently’ before the following Lady Day. The enclosure map of Hackenthorpe from 1797 shows Robinson Close being located to the north of what is now Beighton Road East, and at that time Samuel’s grandson Thomas was still tenant on the land. This land today is occupied by the ASDA supermarket, and a memorial stone in the car park bears keywords and family names linked to the area, amongst them is a stone that reads ‘Staniforth’.

Many publications and documents exist that give us a view of a typical sickle smith’s life from that time period. The building Samuel worked in would have been a long low lean-to building, typically there would be no flooring, so earth was exposed, the roof would usually be tiled however it may have been thatched or likely slated. The interior walls would have been plastered with clay or yellow sludge, made from water and stone dust left over from grinding. There would also be a fireplace in the building which would be found opposite the door with bellows. A stock which was made from a tree stump, usually oak, would be found on the floor. This stock would be buried deep into the earth to give a stable, firm surface. The anvil was then placed onto the buried stock and secured with horse manure. There was unlikely to have been any windows in the smithy, but windows at the time where not made from glass, but oiled paper. There would have been a storeroom which was separate to the main workshop.

By the time August rolled around all of the hay would have been harvested in the fields, farmers would have been finished with their work and the sickles where not in high demand, meaning the workers would have some off time. The 12th of August was generally the end of the Sicklesmiths year, after this time he would either find other work or turn his attention to his farm.

In 1723, a roof loft was being built at St. Mary's Beighton, one of the select few that donated was Samuel Staniforth, who paid £4 10s 0p

In 1727, Samuel sold ‘a messuage, cottage or tenement with part of an orchard’ to Joshua Hancock, this was his sister Rebecca’s husband. We next see mention of Samuel in 1730 when an account was made out ‘of what men and horses has usually been raised within the liberty of Beighton for the Militia and trained band with the value of the free hold Estates’ Samuel’s freehold is valued at 14s per annum. 1733 was when the Open Fields began to be enclosed, ending an ancient system, the shape of the manor of Beighton would be changed forever during this time.

In 1736 a ‘John Blythe; is told to ‘Spread the earth even in Samuel Staniforth’s close called the hole or carry it away before Candlemas Day next, or forfeit the lord of the manor 10s’. The Hole appears on old maps to be near Hackenthorpe Green, on the 1797 Enclosure Map there are closes here named Nether Delves and Over Delves.

Around this time Samuel was paying a total of 10s a year renting out the Grinding wheel on Birley Moor, which was likely the Carr Forge Wheel which stood on the Shire Brook. Today Carr Forge pond can be found in the same spot, with the original wall found to the top of the pond.

By 1740 work would have begun on the buildings that would become the Thomas Staniforth & Co. Sickleworks on Main Street, Hackenthorpe. This workshop would have been built so that sickles could be crafted and sold on a much larger scale than what would have been possible in a small personal smithy. By this time Samuel would have been sixty five years of age so it seems unlikely that he took part in the building himself, but he obviously would have been well aware. It appears that his son John took on the brunt of the work with the help of his brother Thomas who would go onto run and operate the business. The company was officially established three years later in 1743 and the Staniforth’s were granted their own corporate trade mark by the Cutlers Company in Sheffield.

Prior to the opening of the workshops on Main Street, Samuel leased out the new Upper Sickle Wheel at Normanton Springs which also stood and was powered by the Shire Brook. His annual rent was 10s. Today all that remains of this wheel are a pile of ruins in the brook, the area around this section of the brook today is still heavily wooded and the brook runs behind terraced housing, it is not hard to picture Samuel out in this wild area grinding sickles on the brook.

The Memorial wall bearing the Staniforth name in the car park at ASDA, now standing on Samuel's former land.

The Memorial wall bearing the Staniforth name in the car park at ASDA, now standing on Samuel's former land.

The Shire Brook itself played a great part in history to say it is such a small and simply waterway. Not only did this form the boundaries of the manors of Handsworth and Beighton, it also formed the boundary between Yorkshire and Derbyshire and even further back, the brook was the border between the Kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria.

Samuel can be next seen selling property in 1742, he sold ‘The Cliffe’ to a miller by the name of John Taylor. The fact that this sale occurs at the same time his sons are building what would become the family business makes one wonder if the sale was executed as a way to raise additional funds. In 1749 a second sickle wheel was built not far from the Upper Sickle Wheel, this was known as the Lower Sickle Wheel, or Nether Wheel. The remains of the Lower Sickle Wheel can still be seen in the woodland at the bottom of Dyke Vale Road. The area is very overgrown and although an information board was once present, this has fallen into disrepair and the brickwork ruin itself has been covered by foliage.

Samuel’s wife Mary passed away in 1756, with her burial being recorded at St. Mary’s Beighton 22nd December 1754. Samuel would only live a further two years with his burial being recorded 19th August 1756. At the time of his death Samuel must have felt some comfort as he would have seen his sons taking the skills they had learned from him, which had in turn been passed down from his own father and grandfathers, to begin the family sicklesmith. Thomas Staniforth would have had his own son a month prior to his father’s death, Thomas Staniforth II. Samuel must have felt assurance in knowing not only was his son already established in the trade, but that he also had a son to pass down the business too when he too reached the end of his life.

Samuel left behind a quite detailed will and inventory. All four of his sons are mentioned and described as sicklesmiths, John, William, Samuel and Thomas. By this time his daughter Ruth had married Thomas Rowbotham and so is addressed as Ruth Rowbotham, and Mary had married George Rose. His unmarried daughter Sarah is left ‘all the eating stuff which is in the premises’ he then goes onto list meat, bred, cheese, butter, apples and corn. His son John is made sole executor and pays her 15p a week for life. Sarah, it seems, was her father’s housekeeper during the two years between her mother passing away and her father’s death.

The men that took his inventory where his son-in-law George Rose, husband of his daughter Mary, and his friend Joseph Hurt, a man described as a yeoman in his own will. The total value of all of his goods equaled £6, which at the time showed he wasn’t a very wealthy man, especially when compared to his friend Joseph Hurt, whose lavish inventory may have been in part to him descending from the Hurts of Haldworth.

When we compare Joseph Hurts inventory in which he leaves items such as ‘a little tea table now standing in my parlour’ to Samuel who notes ‘One Squared Table, One Stool, One Bason’ we can see that Samuel led a fairly simple life.

Samuel’s homestead at his time of death consisted simply of a single story living room, a parlour and a bedroom over the parlour.

Although Samuel may not have been the wealthiest man in the parish, the legacy he left behind, and the skills he passed onto his sons allowed them to create a business that was to exist for over two hundred years and would see the Staniforth name being sent around the world, stamped on various tools and blades.