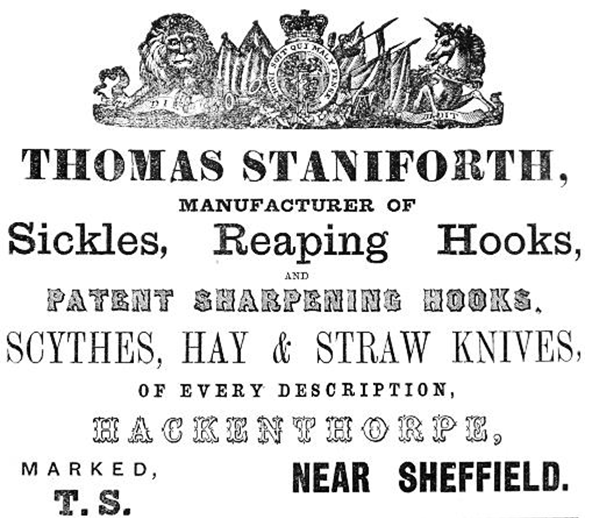

Thomas Staniforth & Co. Sickle works at Hackenthorpe.

George II at the The Battle Of Dettingen

George II at the The Battle Of Dettingen

Sampson Staniforth was baptised on December 30th, 1720. His father Samuel was a Cutler from Sheffield.

It is worth noting that highly regarded researchers such as the late Joseph Hunter in the 1800s were torn on the origins of Sampson, and in his own publication ''Familiae minorum gentium'' he questions whether Sampson was the son of a Benjamin Staniforth, it is likely Mr. Hunter did not have access to the parish records at this time

Sampson lived quite an extraordinary life, and he wrote his own memoirs, however this description of him comes from an 1855 publication by W.C. Wilson titled ''The Friendly visitor''

Extract:

The following history of a soldier, though he lived many years ago, is a very remarkable one, and may be the more interesting at this time, from the circumstances which turn every one's thoughts so much towards our soldiers.

Sampson Staniforth lived in the last century, and was the son of a cutler, at Sheffield. This account of him is taken from one which he wrote of himself in the latter part of his life. He had no moral or religious instruction when a child, and grew up without any fear of God, or any thought indeed of him at all.

He says of himself, that it never entered his mind to think why he was born into the world, what was his business in it, or where he was to go when this life was over; and he grew up in a course of brutal vices, being as utterly without God in the world as the beasts that perish.

He was fierce and passionate, and seemed to have lost all feelings of kindness towards others; so that, instead of weeping with those who wept, he often felt even inclined to rejoice in their sufferings.

At the age of nineteen he enlisted as a soldier, in spite of the tears and entreaties of his mother; and he joined the army in Germany, a few days after the battle of Dettingen. While they were encamped at Worms, orders were read, at the head of every regiment, that no soldier should go above a mile from the camp, on pain of death, which was to be executed immediately, without the forms of a court-martial. This did not prevent Staniforth from straggling from the camp; and he was drinking with some of his comrades, in a small town to the left of the camp, when a captain, with a guard of horse, came to take them up, being appointed to seize all he could find out of the lines, and hang up the first man without delay. The guard entered the town, and shut the gates.

Staniforth saw in time, ran to a wicket in the great gate, which was only latched, and, before the gate, could be opened to let the horsemen follow him, got into the vineyards, where he hid himself, and then got back to the camp.

He had a still narrower escape not long afterwards. Many complains had been made of plunderers in the English Army; and it was proclaimed that a guard would be out every night, to hand up the first offenders that were taken. He listened to the proclamation; and as soon as the officer who read it had turned away, he set off with two of his companions upon a plundering party. They stole four bullocks, and were met by an officer driving them to the camp. Staniforth said they had bought them, and the excuse passed. On the next day the owners came to the camp to make their complaint, and three of the beasts were identified. Orders were, of course, given to arrest the thieves. That very morning Staniforth had been sent to some distance on an out party, and thus, by the providence of God, he was again, preserved from the shameful death.

There was in the same company with him a man, from Barnard Castle, whose name was Mark Bond. "his ways" Staniforth says "were not like those of other men: out of his little pay he saved money to send to his friends. We never could get him to drink with us. He read much, and was much in private prayer."

This good man wished much to be of some use to his comrades. He longed that they should know the same peace of mind that he felt himself, and he saw no one who seemed to be in more need of help than Staniforth. He, as might be expected, first wondered at Mark Bond's conversation, and then mocked at it. Bond, however, was not thus to be discouraged. He met him one day, when he was in distress, having neither food, money, nor credit, and asked him to go with him to hear a sermon which was to be preached that day.

Staniforth made answer "You had better give me something to eat and drink, for I am both hungry and dry." Bond did so; he took him to a sutler's and bought what he needed and then persuaded him, unwilling as he was to go with him to hear the sermon.

Little as Staniforth seemed prepared for it, and little as he expected any such effect, yet it pleased God that, by that one sermon, he should be suddenly and effectually called from a state of brutality and vice, and brought to true repentance for his sin. He returned to his tent full of sorrow, thoroughly convinced of his miserable state, and "seeing all his sins stand in a battle array against him." The next day he went early to a place where he knew some of the soldiers were accustomed to meet, and find retirement for devotion. Here he found some reading, and others were at prayer. One came up to him, and proposed that they should pray together; and Staniforth was obliged to confess that he had never prayed in his life, nor had ever read in any book of Prayers. Mark Bond had only part of an old Bible, but he gave this to Staniforth, saying, "I can do better without it than you."

He was indeed a true friend, he found that Staniforth was in debt, and, telling him that it became Christians to be first just, and then charitable, "we will put both our pays together, and live as hard as we can, and what we spare will pay the debt."

The Battle Of Fontenoy, during the War of the Austrian Succession.

The Battle Of Fontenoy, during the War of the Austrian Succession. Surely Mark Bond had learned to obey such commands as these: "Bear ye one another's burdens, and so fulfil the law of Christ."

"Look not every man on his own things, but every man also on the things of others." And how much less likely he would have been to succeed in endeavouring to do good to his comrades, if he had not set them such an example as this, and shown his love to them by his readiness to deny himself for their sakes!

From that time Staniforth was enabled to give up all his evil habits. Though till then a habitual swearer, he never afterwards swore an oath; though in the habit of drinking, he never was intoxicated again; he had been a gambler, but he now left off gambling; and though he had so often risked his life for the sake of plunder, he would not now take an apple or a bunch of grapes.

Still he remained for a long time in bitter distress under the weight of his sins; but he preserved in constant and earnest prayer to God for his forgiveness, through Christ our Saviour; and at length it pleased God to grant him peace and joy in believing in him. Thus were fulfilled the words of that gracious promise, "Let the wicked forsake his wife, and the unrighteous man his thoughts, and let him return unto the Lord, for He will have mercy on him, and to our God, for He will abundantly pardon" Isa. IV. 7

Staniforth's mother had from time to time sent him money, and such things as he wanted, and she could provide for him. He now wrote her a long letter asking pardon of her and his father for all his disobedience, and telling them that God, for Christ's Sake, had forgiven him his sins. He also desired his mother not to send him anything more, as he knew it must strain her, and that he had learned to be contented with his pay. His parents were very much surprised by this letter, and could scarcely understand it. It was shown to many persons; and being read by some good and king people in Sheffield, one sent him a kind letter of advice and comfort, and a hymn-book; and another a letter, with a Bible, which was more precious to him than gold; so also was a Prayer-Book which his mother sent him.

He came safe out of the battle of Fontenoy, in which Bond also twice preserved in an extraordinary manner, a musket-ball having struck some money in his pocket and another having been repelled by his knife. Soon afterwards Staniforth was drafted into the artillery, and ordered back to England. Before long he married, and intended to obtain his discharge as soon as he could afterwards; but on his wedding-day he was ordered to embark for Holland. The army which he joined there was under the command of Prince Charles of Lorraine. They soon came within sight of the enemy, and Staniforth thought it would not be right to apply for his discharge at such a time. He said he thought it would seem as if he were afraid to fight, and thus he might bring discredit upon his religion.

Near Maestricht two English regiments had a sharp action, and many brave lives were lost that day. Among the fallen was poor Bond. A ball went through his leg, and he fell at Staniforth's feet. "I and another," he says "took him in our arms, and carried him out of the ranks, while he was exhorting me to stand fast in the Lord. We laid him down, took our leave of him, and fell into our ranks again."

Afterwards Staniforth again came where his friend was lying, and when he had received another ball through the thigh; but the French were pressing upon them so closely, that Staniforth was compelled to leave him, thus mortally wounded, "but with his heart full of love, and his eyes full of heaven." "There" says he "fell a great Christian, a good soldier, and a faithful friend."

When the army went into winter quarters Staniforth bought his discharge with money sent to him by his wife, who possessed some property. He now settled near London, and passed the rest of his life in useful employment, spending all the time he could in endeavouring, in various ways, to do good to others.

The course of his life and the happy state of his mind are thus described by himself "I pray with my wife before I go out in the morning; and at breakfast time, with my family, and all who are in the house. The former part of the day I spend in my business, my spare hours, in reading and private exercises. I conclude the day in reading the Scriptures, and in praying with my family. I am now in the sixty-third year of my age, and glory be to God, I am not weary of well-doing. I find my desires after God stronger than ever; my understanding is more clear in the things of God, and my heart is more united than ever both to God and His people. I know that religion is the gift of God through Christ, and the work of God by His Spirit: it is revealed in Scripture, and is received and retained by father, in the use of all the ordinances of the Gospel. It consists in deadness to the world and to our own will and devotedness of our souls, bodies, time, and substance to God, through Christ Jesus. In other words it is the loving the Lord our God with all our hearts, and all mankind for God's sake. This arises from a knowledge of His Love to us: we love him, because we know He first loved us; a sense of which is shed abroad in our hearts by the Holy Ghost that is given to us. From the little hereof that I have experienced, I know he that experiences this religion is a happy man."

So concludes the account we have of Staniforth. I trust that among our soldiers (some of whom may perhaps read this) many are endeavouring to follow such examples, and know by their own experience the happiness of so living in the love and service of God. Or if they have not yet thought much of religion, may they now begin in earnest to do so, and to pray to God for His Holy Spirit, that they may truly turn to him!

May more and more of the brave soldiers of England become the true soldiers of Christ; so that, whether they close their eyes, like Staniforth, in peaceful homes, or fall, like Mark Bond, on the battle-field, they may die as he did, full of holy love, and of the blessed hopes of heaven, through Jesus Christ our Lord!

End of Extract

Sampson's wife was Mary Hutchinson, whom he married on the 12th June, 1746 in London. He was buried on the 6th March 1799 at City Road, London.