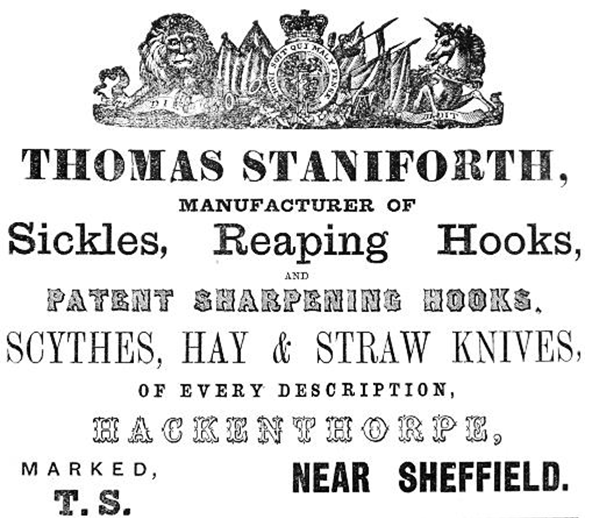

Thomas Staniforth & Co. Sickle works at Hackenthorpe.

Dr. John William Staniforth c1915

Dr. John William Staniforth c1915

John William (Jack) Staniforth was born in Sheffield in 1863 to William Staniforth and Sarah Parkin. At the age of nine he was sent off to a school for small boys and girls run by a Miss Belk, at the top of Oxford Street. The following year he moved to Milk Street Academy, which was what he called a ‘private-adventure school’ run by Mr. Richard Bowling, and in 1874 he joined the Sheffield Royal Grammar School, of which he writes: ‘One does not like to speak ill of one’s school, yet truth compels me to say that the Grammar School was not a good school. Its tone was bad. Its teaching was superficial and without system.’

His first day started badly. During prayers, while every boy stood, cap in hand, alongside his ‘play box’, which contained his books, slate, pencils and pens, (the boy next to Jack muttered, ‘That’s not a seal-skin cap. It’s a cat skin!’ This base suggestion was vehemently repudiated, and consequently Jack was sent for, accused of talking during prayers, caned, and went home tearful and mortified.

When his schooling was completed, his father wanted him to learn the trade of silversmith at Fentons and then to assist him in starting in business on his own again. Jack was determined to become a doctor and viewed working at Fentons with distaste. After much discussion a compromise was reached. Jack would go to Fentons for a year, if he liked the work he would remain; if he still wanted to take up medicine he would be allowed to do so. In March 1880, therefore, he began to accompany his father to the South Moor Works each morning.

‘You must not run away with the idea’, he is at pains to make clear. ‘…that I went into the shops and worked at the bench. My father (who was now practically Manager) had a room adjoining the die-sinkers’ shop, where he made designs and calculations, modelled, interviewed customers, travelers and workmen, and wrote letters. In this room I also wrote letters, and did some amateur modelling, and made copies of designs and checked invoices and cast up long columns of figures. Naturally, I went into the shops at odd times, and tried my ‘prentice hand at soldering, stamping, turning, pressing, hammering, die-sinking and even electro-plating and gilding… I did not receive any wages, but my father increased my pocket money to two shillings a week, out of which I was expected to buy gloves, collars, ties, papers, stamps and presents!’

By Christmas, it was clear that this arrangement was not a success and William told his son that he need not return to Fentons and, in 1881, he joined the Sheffield Medical School.

It may be that in an attempt to dissuade Jack from a medical career, William had said something like: ‘Doctor? Why do you want to be a Doctor? There are no doctors in the family. Silversmiths, Sicklesmiths, publicans, but not doctors.’

Not in the immediate family perhaps, but there had been Staniforths, who were medical men. The one most celebrated in his time was William Staniforth, one of the three original surgeons appointed to the Sheffield Infirmary when it opened in 1797. We have an article on this William Staniforth here.

A cobbler from Woodhouse wrote the following lines, supposedly about a mysterious Dr. Staniforth, fat and fond of good living, who lived at Beighton Bridge:

It happened on a certain day

I met two asses by the way

The one he had so gorged his hide

Upon his brother, was forced to ride

Was forced to ride upon his brother

A greater ass than the other.

By 1888, Jack was in poor health following the death of his mother, however he now had both his longed-for diplomas under his belt. Towards the end of the previous year, an epidemic of smallpox broke out in Sheffield and within months this had assumed alarming proportions and the Fever hospital in Winter Street found itself overwhelmed. A hospital was set up temporarily at Totley, just outside the town. The site that was taken over for the purpose was known as Victoria Gardens and it underwent a bizarre change of use, for there had been opened there five years earlier what Jack describes as ‘a kind of dancing-saloon and theatre of varieties combined’ comprising a ballroom, refreshment room, a menagerie, facilities for archery, cricket and tennis. There was also boating on the lake. The programme for the opening day had included negro comedians and dancers and a slack wire walker, as well as gymnasts and ‘Serio-comic vocalists’; there was to have been an ‘explosives exhibition’ but this was cancelled and bad weather caused the postponement of a promised balloon ascent. The whole enterprise, however, ended in the Bankruptcy Court and the pavilion, which was mainly constructed of glass, was now standing empty. Curtains were hung and wooden partitions erected to divide it into men’s and women’s wards, doctor’s surgery, a matron’s room and so on. Here Jack was installed as Medical Officer and wrote plaintively: ‘Needless to say nobody ever came to spend an evening with me, and whenever I showed my nose outside the four walls of the grounds, the inhabitants of the neighbouring village incontinently fled into their houses, and peered at me over the top of the window-blinds!”

He goes on to say ‘Being thus entirely thrown upon my resources, I took to writing stories,’ He did this to such good effect that, over the course of the next thirty years he became increasingly known as an author of boy’ stories, creating several fictional detectives, the best known of whom was Nelson Lee, and writing thirty-two of the Sexton Blake stories, after which ‘out of sheer weariness and despite the editor’s appeals, declined to do any more. The series was afterward continued by other writers.’ Sexton Blake, in fact, survived until the 1960’s. Jack was a great admirer of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and aimed to do for boys what Conan Doyle had done for his adult readers. In all his stories he strove for complete accuracy and his street names, hotels, steamship sailings etc. were always authentic. He used a number of pen names, most frequently ‘Maxwell Scott’, which combined the maiden name of the girl he married with the name of an old friend of his.

When the Totley hospital closed, which it did after five months, he set about looking for a practice. Unfortunately, he was diagnosed as having a ‘patch on his lung’ and advised to leave the smoke of Sheffield and find work elsewhere, preferably by the sea. In 1891 he was offered the position of doctor in the Grinkle-Ironstone Mines at Hinderwell which he could combine with being a G.P.

This he accepted. Yet, when Jack told his father proudly of his appointment and his imminent departure into general practice, in the confident though unspoken expectation of a financial contribution - £200 perhaps – well £100 – surely £50 – William refused to discuss the matter with his son. He never explained the reasons. Perhaps it was because Jack had confided first in his sweetheart May Maxwell, who was a nurse, and not in his father, perhaps it was because he had not got even the £50 which was so sorely needed, but was too proud to say so. Perhaps it was both, Jack’s worldly capital amounted to half a sovereign, three half crowns and one shilling, total 18s 6d. He borrowed two pounds from his sister Mary – all the money she had – and after paying the cab and his railway fare to Whitby, upping the porter and sending a wire to his employer, he set out with £2.6s.0d with which to find accommodation and possibly furnish it, and buy a stock of drugs and keep himself until some money started to come in. By a mixture of bluff and good fortune, he succeeded. Loftily he turned down the only vacant house to rent as being too small and took rooms. The out-going doctor’s stock of drugs was left at his disposal (It included nearly a pint of laudanum) and he learnt with delight that the miners’ fortnightly contributions of 6d per head from each married man and 3d each from the unmarried men were paid by the mines cashier straight away to the doctor, and not accumulated for three, six or even twelve months. The new doctor was in business.

However, these early months in Hinderwell were lonely and difficult ones. He had little money and as yet no friends. Whenever he had any money at all to spare he spent it on the fare to Wrexham where May was nursing. He was not feeding himself properly; he could not afford to buy himself new boots. Before long his health started to deteriorate; he lost weight, he coughed all the time, sometimes coughing blood. In his own words ‘the grisly spectre of consumption once more raised his head’.

When he could no longer ignore these symptoms, he travelled up to London and consulted a specialist at St. Thomas’ Hospital who had no hesitation in saying that Jack should throw up the Hinderwell practice and move somewhere the climate was warmer, like the south of France. But how could he support himself in the south of France? How could he ask May to marry him in these circumstances, and why should she wait for him? He told her she must consider herself released from her engagement. She, however, suggested that they should marry and then, if Jack had to go abroad, they should go together and live on her own small capital. Jack was touched, but would not hear of it. And yet, he writes, he did not like the idea of ‘some other man running off with her whilst I was away.’

Eventually May persuaded him that they should marry, but no one was to know until Jack was in a position to offer her a home. So on 17th November 1891 they tied the knot at the Registrar’s Office in Whitby with no fuss or ceremony and afterwards Jack returned to Hinterwell and May went back to Wrexham.

After a few days, first one person and then another congratulated Jack on his newly marred status. How did they know? They had seen it in the paper. How had the paper got to know of his marriage? It was simple really; the Assistant Registrar’s brother edited the Whitby Gazette and knowing of no reason why he should not do so, the Assistant Registrar had passed on this item of local news.

The Gazette was seen in Sheffield. A copy found its way to Wrexham. Their secret was well and truly out. Jack had to put up with a certain amount of teasing, but whether because there was some rule forbidding married nurses or whether the Wrexham Infirmary Matron felt May should have asked her permission or at least informed her, for whatever reason, May was dismissed.

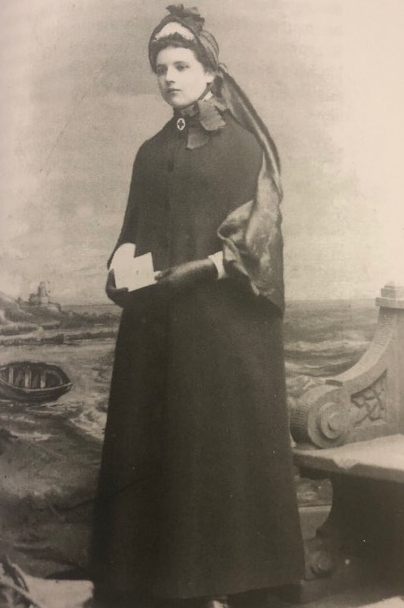

May Staniforth (nee Maxwell)

May Staniforth (nee Maxwell)

This was serious, Jack was due to visit the consultant again and when he did so he told him flatly that he would not go abroad, he was now married and he and his wife intended to settle in Hinderwell. Faced with this decision and sensing that the situation was altered in that Jack now had someone to look after him, the specialist offered no further objection.

At May’s insistence, they were married a second time, this time ‘properly’ in St. George’s church in Sheffield, and after their honeymoon she stayed with her in-laws until Jack had arranged the formalities on a house he was to rent for fifteen shillings a week, and came to collect her and bring her home.

Jack remained in practice at Hinderwell until not long before his death in 1927. For many years he had to endure outright hostility from a rival practitioner, though he gained for himself a place in the hearts of the people of Hinderwell and the neighbouring villages. Many of his bills, if paid at all, were paid in kind, in the form of home-grown vegetables, or fruit, or a rabbit for the pot, or, in the case of the members of the artists’ colony at Robin Hood’s Bay, two of whom, Spencer Ingall and Frederick Jackson, became godfathers to his children, a picture.

He made his rounds by pony and trap. Journeys to Whitby and longer excursions back to Sheffield and occasionally to London were made by railway, on which the service was still in those days inexpensive and frequent both on branch and main lines.

In August 1914, the doctor describes in his journal the shock he felt by the nation at the declaration of war. ‘Many of us – I for one, certainly, - had long believed and preached that it was unthinkable that the civilized nations of the earth, especially the so called Christian nations, should never again settle their disputes by means of a bloody war. And lo! In the short space of four days [Germany had declared war on Russia on the 1st August and on France on the 3rd, on 4th England declared war of Germany] all our theories were demolished and the leading nations of Europe – the very cream of Christian civilization – were already either engaged on the work of slaughter or feverishly preparing for it!’

The most immediate effect the war had locally was to cause the disappearance of flour from the grocers’ shelves. Jack, however, ran to earth three stone of flour in nearby Staithes, which he brought home in the trap, thus averting the threat of a bread famine in the household.

On 16th December Whitby, together with Scarborough and the Hartlepools, was shelled by German cruisers, and Jack hurried into the town to see if he could render assistance. One coastguard had been killed and a boy-scout wounded and a number of houses partly demolished. Later, German airships were to bomb repeatedly the nearby mining village of Skinningrove, where explosives were manufactured, and on one occasion, a submarine attacked the Staithes fishing fleet.

In April 1915, Jack volunteered for the R.A.M.C, on condition he was sent to the front. His son, Max, had been in the army since soon after the outbreak of war and the following year Jack’s young brother Carll, christened Carnall and seventeen years his junior enlisted as a private in the Motor Transport section of the Army Service Corps, and after a few months’ training was sent to Mesopotamia. Not surprisingly, Jack’s offer was turned down on account of his age.

Like his father he was a family man, intensely proud of his children’s accomplishments. His journal is illustrated with snapshots of the children. There are pictures of two-year-old Max, sitting in a little basket-ware ‘chair-saddle’ on the donkey, Dodo; of the two girls Mary, known as Maisie, and Maureen astride another donkey, Billy. Seemingly there was always a donkey for the children, one of them – the story goes – so conditioned by a previous owner that he resolutely halted at the doors of any public house which lay on his route. Later there are pictures of Maisie dressed for her confirmation. Maureen learning the violin, Max in his uniform as a 2nd Lieutenant.

Again like his father, the doctor was a keen Liberal, indeed he was asked to stand as a Liberal candidate, but this request he declined.

Towards the end of his life he contracted Parkinson’s Disease, then known as ‘paralysis agitans’ or ‘Shaking Palsy’. For some tears his wife had suffered chronic ill health. This and recurring financial problems go a long way to explaining his periods of pessimism and depression, but I believe they were largely a legacy from his father and an inheritance – which he passed on to his son and daughters.

The girl he had married in 1891, May, was born Mary Jane Dobbin Maxwell, grand-daughter of the prolific and colourful Irish author, William Hamilton Maxwell, who wrote Life of the Duke of Wellington, Wild Sports of the West of Ireland, and many other books. She had been born and brought up in County Cavan and had nursed at the Rotunda in Dublin. She had been engaged to be married to Dr. James Craig, later Sir James Craig and a member of the Dail, but she broke off this engagement, when she met Jack Staniforth. May left Ireland after her step-brothers and sisters were orphaned and sent to England to be adopted. Jack’s devotion to her lasted all his life, he filled a leather bound book with love poems to her in his youth and later agonized over her failing health. He died at the beginning of 1927 at Bamford where he had moved when he retired, but he is buried at Hinderwell, as is his wife who survived him by seven years.