Thomas Staniforth & Co. Sickle works at Hackenthorpe.

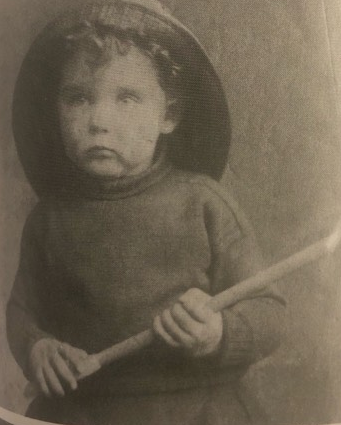

John Hamilton Maxwell Staniforth, 1914

John Hamilton Maxwell Staniforth, 1914

John Hamilton Maxwell Staniforth was born in 1893, the son of John William Staniforth and May Maxwell. He was named Maxwell for his maternal great-grandfather, Irish Poet William Hamilton Maxwell, and was known for most of his life as Max.

He and his sisters enjoyed a happy and carefree childhood. At a time when girls were more often restricted by black stockings, and starched pinafores and boys by boots and knickerbockers, they and their Newell cousins were allowed to run about bare legged, very often with bare feet, clad in nothing more formal than short smocks. When he was nine, however, Max was sent away to preparatory school.

His father, we know, considered his own schooling superficial and inadequate. During his time at the Sheffield Infirmary, he had made a friend of, and been greatly influenced by, a young house surgeon called Fred Coombe, whom he describes as being ‘my beau-ideal of an English gentleman’. He embodied for Jack the so-called public school ideals and opened the door of a new world – a world in which money was not everything, in which vulgarity and meanness were held in detestation, in which honour and truth were the all-presiding deities. He also unraveled for Jack the intricacies of such things as dinner menus, the proper hour at which to pay a social call, and when you might and might not shoot various species of game.

So, twenty years on, it was a proud day for him when in September 1906 he accompanied Max to Charterhouse where he had won a scholarship. A similar award from Shrewsbury the previous year had been turned down by his preparatory school headmaster as being of less financial value to the family.

Towards the end of Max’s school years, his father was becoming increasingly short of money. The 1911 National Insurance Bill threatened to reduce his medical income, his writing was not bringing in as much as it had done earlier and, besides the expense of his wife’s illness, he was helping to support two of his sisters. So Max decided, instead of heading for Oxford, to leave Charterhouse and go out into the world and get a job. However, he was eventually dissuaded from such a course and went in for and won the top classical scholarship at Christ Church, where he went in the autumn of 1912.

He was almost certainly destined for an academic career but for him, as for the rest of his generation, the Great War changed everything. War broke out at the beginning of Autumn 1914, shortly after his twenty-first birthday, and found him engaged as a tutor at Grassington, near Skipton, so it was not until October that he was free to join up. Then he enlisted with the Connaught Rangers, the old 88th Foot, believing that his great-grandfather William Hamilton Maxwell had served with that regiment in the Peninsular War, which was what his Irish namesake wished his readers to believe. Unfortunately there is no historical basis for this. In any event a month later Max was commissioned and joined the 7th Bn Leinster Regiment and he served with this battalion until it was disbanded. All through the war he wrote frequently and at length to his parents. His letters describe graphically both a period of training raw recruits in County Cork, and their subsequent life in the trenches. During the fighting on the Somme in 1916, the 7th Leinsters took part in the assaults on Guillemont and Ginchy, bloody battles which cost the battalion very heavy losses.

Ideals were still unsullied in 1914. Max writes of his fellow subalterns, most of whom were hardly out of the teens: ‘There’s something tremendously attractive about the average officer – I think because he has always to be setting an example to the men. The men are always watching and you wouldn’t believe the number of little things, quite ordinary, that one refrains from doing under their scrutiny. And of course you can’t afford to be the smallest bit careless of your personal appearance: a shave twice a day, hands washed every hour, boots always clean, buttons always shining till you can see your face in them – in fact, up to concert pitch always. It’s very trying but it produces very fine results.’

Over the coffee and cigarettes after dinner, the pipers entered and marched round the dinner table, the Leinsters being one of the pipe regiments: ‘ I feel much prouder of saying “I’m in the Army” than I did of saying “I am at Christ Church… or Charterhouse”… But the Army is a man’s work so emphatically, and I suppose that’s why one is proud of doing one’s little bit. IT gives you self-respect.’

Soon he was off on a signaling course, at Waterford. Then followed maneuvers ‘…among the mountains and the bogs… We were a most imposing column on the road: first the band – flutes, drums and pipes – then the signalers, then the scouts, then the main body – four full companies of very dusty Tommies in full marching order (packs, straps, bandoliers, water-bottles, great-coats, mess-tins and rifles and bayonets: the whole Christmas-tree), then the machine-gun section with their spidery little guns and spidery little officer, then the transport and drivers apiece, and a couple of little timbered wagons with officer’s transport and rations – and finally the baggage-guard and stretcher bearers. We took up about ¾ a mile all told.’

By the end of November 1915 they were at Blackdown Camp near Aldershot and by Christmas they were in France and ‘the keynote of the whole thing is boredom and weariness, utter and absolute. You sit in a dug-out and read or play cards from morning till night, and your nerves get worn out with watching against Hun attacks which never come, and with shoring up parapets that crumble in even as you dig, and pumping out water that fills up again as fast as you get it out.’

No longer were the boots clean and buttons shining: ‘The water in some places was up to the thighs, and nowhere under the ankles, the wet walls of the trench smeared one all over as one pushed along between them; so you can believe that when men come out after four days on duty there is absolutely nothing to be seen of man, uniform, cap, equipment, face or rifle. And the mud is of every consistency, from the thin gravel that is half water to the still gluey clay that pulls the boots off your legs.’

He describes approaching the front line: ‘Imagine a vast semi-circle of lights; a cross between the lights of the Embankment and the lights of the Fleet far out at sea; only instead of fixed yellow lamps they are powerful white flares, sailing up every minute and burning for 20 or 30 seconds, and then fizzling out like a rocket – each one visible at 10 miles distant, and each lighting up every man, tree and bush within half a mile. Besides these you will see a slim shaft swinging round and round amongst the stars, hunting an invisible aeroplane: and every instant a ruddy glow flashes in the sky like the opening of a furnace door and there is a clap of thunder from the unseen “heavies” (shells). The whole makes a magnificent panorama on a clear night. Then you’d step down into a trench, and that would be your last breath of open country for sixteen days… The rest of your time would be spent in a world of moles, burrowing always deeper and deeper to get away from the high explosives; an underground city with avenues, lanes, streets, crescents, alleys and cross-roads, all named and labelled and connected by telegraph and telephone.’

As a Signal Officer, he spent a lot of time laying or mending cables: ‘The job no one likes is mending wires… the same explosion shattered my wires. So I had to mend them – all covered with fresh blood – and you should have seen me kneeling there under the parapet, working for dear life with pliers and insulating tape and smoking a feverish cigarette trying hard to forget that rifle-grenades are fired from a fixed tripod and at the same range, and that they would probably send over two or three more into the same place in the next few seconds.’

Max c1895

Max c1895

Amazingly, all through the time he spent in France, Max received parcels from home, containing not only such ‘comforts’ as socks, mittens, cigarettes, a new pipe and an air pillow, but cakes, pastries, honey, pork pies, bacon, and egg, which speaks well of the Post Office.

This, when all was said and done, was an Irish battalion. Corporal Chievers had to take four men and cast bombs from a sap-head. ‘Corporal Chievers knew very little about bombs but a lot about the duty of setting a good example. So he withdrew the firing-pin and advanced gingerly up the sap, and the four tip-toed behind him, open-mouthed, and heart-throbbing. They arrived at the sap-head: Brother Hun a bare sore of yards away, Corporal Chievers took a deep breath. “In-the-name-of-the-Father-and-of-the-Son-and-of-the-holy-Ghost” said Corporal Chievers, crossing himself wildly, and cast the bomb into space..’

The same pipes which had accompanied the after-dinner coffee back in Ireland. ‘…lifted the Irish out of their trenches and sent them over the parapet. I don’t know how many times those wicked little war-pipes have played up and down the glens of Munster, but they never did better work than when they played the Leinsters forward and set them racing straight in the teeth of the Prussian Guard.’

Following the Easter Uprising in Dublin in 1916, the Germans tried to undermine their morale by putting up placards, which said ‘Irishman, Great Uproar in Ireland. English guns are firing on your wife’s and children. Throw your arms away. We will give you a hearty welcome. ’To which they replied by playing ‘Rule Britannia’ and lots of Irish airs on a melodeon in the front trench to show them we weren’t exactly down-hearted.’

By this time he was not only verminous like everyone else, he was suffering so badly from scabies that he was sent to hospital, from which he was discharged at the beginning of September 1916, just when the order came through ‘The Brigade will take Guillemont’. ‘And by God we did it’, he writes.

They were ordered ‘up and over’ and walked through the machine gun bullets and ‘the air was just one loud noise – like moving in a kind of sound box’. They sheltered in a German dug-out and were sent back for 48 hours ‘rest’ in the trenches which were ‘simply hen-scratches here and there in an area of absolute desolation, swept day and night with incredible tornadoes of shell fire.’ ‘Then they brought us up again to finish the job and take Ginchy.’ Again they had to walk, this time about seven hundred yards, with men ‘…dropping like flies all round. I saw the most awful sights then.’ And the wounded had no way of getting back except over the open. It was then that I got knocked out.’ When he came to, on a stretcher, he was told that the Germans were beginning to counter attack and the line had to be held. ‘…till the last man was dead, There were we, just a battered handful, many of us wounded, crouching there in a few shell holes in the middle of that tearful shell-swept desolation at midnight, some of us with revolvers, some with rifles we had snatched up, some with ammunition taken from the dead men; just waiting and watching. I saw fifty men wiped out in ten seconds by a machine-gun at one point; they simply melted away and dropped before you could realize where they had gone. Excepting headquarters, myself and one other were the only officers who came back of those that went over. All my old friends – all those who were with the battalion at Fermoy and Kilworth… the general came round and made us a speech: “fresh battle honours for the colours” , “heroes of Guillemont”. But that doesn’t make up for empty chairs. I haven’t told you half of what really happened, because I can’t. Things like that can’t be described.’

The winter of 1916-17 was bitterly cold and in March Max, exhausted and run down in health, was sent on extended leave and then posted for a few months in a reserve battalion in Limerick, but by May he was back in the trenches preparing for a new offensive which was to go down in history as Third Ypres or notoriously, Passchendaele. They practiced the coming attack ‘forwards, backwards and upside down, till we could do it in our sleep’, ‘Our preparations are colossal, and undreamed of before, dwarfing our previous offensives to insignificance.’ He wrote. And yet the horror of their ensuing battle was such that the Commanding Officer, Colonel G.A Buckley wrote of the Leinsters, ‘Guillemont and Ginchy was a drawing room entertainment by comparison with what we went through’ and that there now remained ‘only a shell of a battalion’.

The following winter was as severe as the previous one had been. Snow drifted six feet high, milk and even whiskey froze solid. Max was now Quarter Master and Acting Adjutant. At the end of January 1918, the battalion was deeply shocked to learn it was to be disbanded and Max was among those who became part of the 19th Entrenching Battalion, in which he refused the offer of a captaincy.

In March there was a major German offensive. Max was away from the line at the time, and wrote briefly home on Easter Day: ‘The 116th Irish Division has ceased to exist. Wiped off the map. You know where they were; they took the Boche attack full smack, the first day they were in the trenches. They died fighting, while I was hanging round a base depot. I’ll tell you about it later. I don’t want to just now.’

If he felt angry at not having been there and guilty at having survived, his turn was not long in coming. In the last summer of the war he was severely gassed. ‘I made an awful idiot of myself, hobbling round on my orderly’s shoulder like an asthmatic old man of eighty. However, that was all right; gassed folk are common enough nowadays and no one thought anything of it. But then one of the offiers asked me some commonplace question about something and instead of answering I looked at him for a minute, and then my face screwed up like a baby’s, my lip quivered, and I dissolved in floods of tears! I remember crying piteously and imploring them not to go round that way [past several heavy batteries] and hiding my face and cowering when the bang came. It was a very degrading exhibition.’

He was relieved to be told later that this sort of breakdown was a not unusual symptom of Dicholorethylarsine gas. At the beginning of June he was sent back to England, to hospital in Denmark Hill in south London, and he never returned to the trenches. He was not fit for active service again until August when he was sent to Fort Nelson above Portsmouth.

As early as February 1915, Max wrote to his mother ‘I’ve been looking back on myself as I was two years ago, and I think I’ve changed a good deal, Not necessarily for the better, I mean – in several ways probably not – but I’ve learned a heap of Life. I wonder what you’ll think when we meet again.’

If this was true then, how much truer it must have been by the time the war finally came to an end. Of course, he and thousands of young men like him had changed – how could they not, having lived for so long lapped by a tide of carnage, which, for its scale and its depravity, has been compared to the Holocaust?

While he was at Fort Nelson, he met a Naval Paymaster-Captain’s daughter, Ruby Di Stephens, who was serving as a Wren in the Paravane Department, After a two-month courtship, while Portsmouth was ravaged by Spanish Influenza, they became engaged. Known to her family as Biddie, he later preferred to call her Dinah. In her diary she describes having met: ‘..a very nice Irishman (sic).. regular features and dark hair and mustache. He bathed with us but nearly collapsed afterwards. He’s only 3 weeks out of hospital and has been very badly gassed.

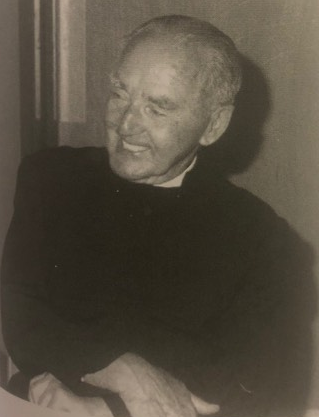

Max in 1977

Max in 1977

That was August; by October she confessed herself ‘the happiest girl in the world – it’s much too wonderful to write about’ They were very much in love.

With peace came the need to find work. Max took a job with a coal-shipping business and after their marriage he and his wife moved to South Wales. The firm trained him as an engine driver, the better to demonstrate the quality of their coal, and at the time of the General Strike in 1926 he volunteered to drive a locomotive for the Great Western Railway. He was sent to work in Neath where he had to bring his engine up from the engine sheds along a short spur line which ran behind a row of railway men’s cottages, effectively running the gauntlet of local strikers. One of the strikers had purloined his young son’s catapult and used to take pot shots at the engine driver and the fireman. At the start of the strike his arm was not good, but after a week’s practice he had improved remarkably, forcing driver and fireman to take cover, prone on the footplate when they passed.

Then he went to Argentina where he joined the Entre Rios Railway for which he worked until 1931, when world depression meant that he was again looking for work. ‘Max axed’, wrote Dinah in her tiny pocket diary. They sailed home to England and for six months he wrote letters, called on people, pawned his cuff links, went for interviews. Hopes were raised, then dashed. Two days before Christmas he got a job under Captain Leonard Plugge with the International Broadcasting Company at Radio Normandy in Fécamp. ‘25th December Such a happy day’ wrote Dinah. On Boxing Day Max left for France; three months later his wife and small daughter joined him and they lived in rooms until October when they were able to rent a small furnished house. The following month they were told they were to leave Fécamp, which they did on 21st December. So ended Max’s career as an announcer, mostly spend announcing dance records. In 1983, when the BBC were compiling a programme to commemorate half a century of popular music on the air, they prevailed on him to take part, dubbing him, not entirely accurately the first Disc Jockey. He continued to work for the IBC until the early summer of 1932 when Plugge, it seems, had no more use for him. The same pitiless round of applications and interviews recommenced.

He managed to find a job with a publishing firm, working long hours with little security. Then Dinah was diagnosed as a diabetic. Her health had been poor for a long time. Now her weight was down to under five stone. She was taken into hospital and the then quite new treatment with insulin started. When she was stabilized, Max finally bowed to an increasing inner compulsion and enrolled at Chichester Theological College at what was considered the advanced age of forty-three. In 1937 he was ordained and thereafter served in a number of country parishes, all in the south of England. Besides, a committed faith he brought to his work a deep love of the ancient Sarum ceremonial of the Anglican-Church and also an at-homeness or at-one-ness with rural village life, a sort of echo of the days when, as a boy, he had followed his father on his rounds in and out of the cottages in Hinderwell. But if the economic climate had not been so harsh in the thirties and jobs been easier to get, the Church might have lost a valuable priest, and Max might not have found so worthwhile an outlet for his undoubted gifts, or not then anyway.

Another war came and went. Living at that time on a few hundred yards from the south coast, he watched the troops returned from Dunkirk, shocked and exhausted. For a while he and his wife and daughter were under Instructions to pack up and be ready to leave home within twenty-four hours, under the threat of a German invasion. Max donned a tin helmet, fought incendiary bombs. A year or so later he moved to another parish on the border of Kent and Sussex, which in 1944 acquired the dubious distinction of having more flying bombs shot down over it than any other. He became one of the official ‘triumvirate’, appointed to organize the village in an emergency. These three were, as seemed proper at the time, the squire, the doctor and the parson. Then a flying bomb, or ‘doodlebug’ fell just outside the garden fence and although Max and Dinah were unhurt, the vicarage was too badly damaged for them to remain there, and they became refugees, dependent on the generosity of neighbours.

There were more moves before the time came for retirement in 1963. Now Max turned his attention and his abiding interest in the classics to the translation of the ‘Meditations of Marcus Aurelius’ and the ‘Early Christian Writings of the Apostolic Fathers’. One of the recurrent themes of the Meditations is the brevity of life. Again and again Marcus comes back to this ‘All things are born to change and pass away and perish.’ ‘How small a fraction of all the measureless infinity of time is allotted to each one of us: an instant and it vanishes into eternity’. ‘Despise not death, smile rather at its coming, it is amongst the things that Nature wills.’ These counsels did little to comfort him when Dinah died in 1970. She had been a gallant companion for over half a century, skilled at turning houses into homes, re-creating gardens which always seemed to have been left untended and uncared for, never complaining about the restrictions of her diet or her increasing frailty, and her death shook Max badly.

He himself died on Boxing Day 1985, seventy years almost to the day since his arrival in the trenches as a junior officer in 1915. Four years is not long in a lifetime which spanned more than nine decades, had included many moves and had not been without incident, but the memory of his service in the army remained largely undimmed until the end, although he seldom spoke of his experiences. After his death, there was found carefully put away in an old oak bureau, which had been his father’s and before that his grandfather’s. not only copies of his Great War letters, his certificate for gallantry, his Officer’s Record of Services, demobilization papers, various railway warrants and buttons, and cap badges, but a list of forty-two items such as battle maps, secret codes, service postcards and photographs, which he had given to the Imperial War Museum, together with original letters.

Other memories reached further back: to his childhood. After the end of the Second World War he saved up his petrol ration and took Dinah and his daughter up to visit Hinderwell. He found it much changed in ways that saddened and hurt him but he wrote, in a letter to his sister Maisie: ‘Never the less, there were some things from which the virtue had not wholly departed. There is still the unchanging skyline of the quiet circle of hills that looks down, enfolding the whole countryside in its gracious curve, from Kettleness right away round to Boulby, with the remote little farmsteads, sleeping on the hillsides, and the lights and shadows chasing each other over the whole ten mile sweep, so that I found it still possible to say, as mother used to say I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills from whence cometh my help.’ Bit, standing in the garden of his old home and seeking the ghost of the boy he once was, he quoted Robert Louis Stevenson, and added wistfully:

‘He has grown up and gone away

And it is but a child of Air

That lingers in the garden there’